Brought to you by the National Eye Institute (Bethesda):

There are many South Africans who have either Type I (juvenile onset) or Type II (adult onset) diabetes. All are at risk of developing sight-threatening eye diseases that are common complications of diabetes. Although early detection and timely treatment can substantially reduce the risk of severe visual loss or blindness from diabetic eye disease, many people at risk are not having their eyes examined regularly to detect these problems before they impair vision. Increased awareness of the sight-saving benefits of annual eye examinations through dilated pupils is essential to reduce the significant social and personal costs of diabetic eye disease.

What is Diabetic Eye Disease?

Diabetic eye disease refers to a group of sight-threatening eye problems that people with diabetes may develop as a complication of the disease. They include:

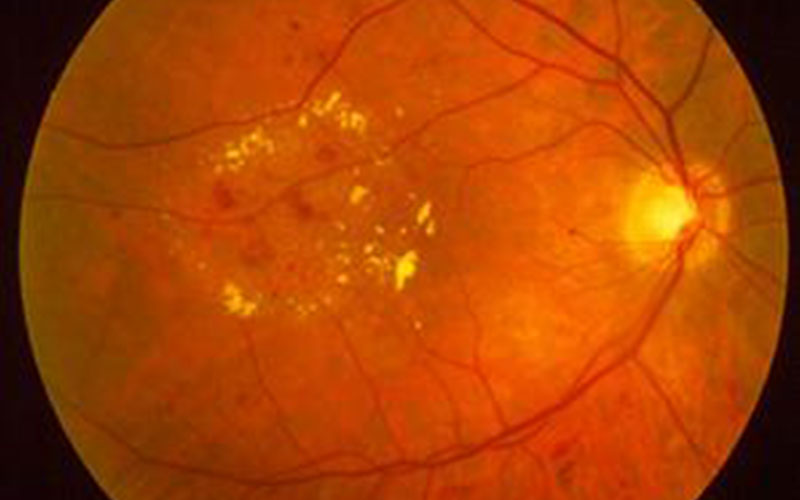

- Diabetic retinopathy. This disease damages blood vessels in the retina, the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye that translates light into electrical impulses that the brain interprets as vision.

- Cataract. A cataract is an opacity of the eye’s crystalline lens that results in blurring of normal vision. People with diabetes are twice as likely to develop a cataract as someone who does not have the disease. In addition, cataracts tend to develop at an earlier age in people with diabetes, around late middle age.

- Glaucoma. This disease occurs when increased fluid pressure in the eye leads to progressive optic nerve damage. People with diabetes are nearly twice as likely to develop glaucoma as other adults.

Cataract and glaucoma also affect many people who do not have diabetes.

What is the most common Diabetic Eye Disease?

Diabetic retinopathy.

Although anyone with diabetes can develop diabetic retinopathy, research shows two important risk factors: (1) type of diabetes, and (2) duration of disease. People with Type I diabetes are generally more likely to develop diabetic retinopathy that Type II patients. In fact, virtually all people who have had Type I diabetes for 15 years or more have some degree of diabetic retinopathy. Among people with Type II diabetes, duration of disease is also an important risk factor. Insulin-taking Type II patients who have had diabetes for 5 to 10 years have about a 2 percent incidence of proliferative retinopathy. This rate increases to more than 50 percent in insulin-taking Type II patients who have had diabetes for more than 20 years.

How is Diabetic Eye Disease detected?

Because diabetic eye disease often has no early symptoms, it is detected during a comprehensive eye examination through dilated pupils. Dilation consists of the eye care professional’s placing medicated drops into the eye to enlarge the pupil. By doing so, the practitioner can better examine the back of the eye for early signs of disease, such as microaneurysms, before noticeable vision loss occurs.

For example, if the eye care professional detects diabetic retinopathy early, he or she can then monitor the patient’s condition and determine the best time to treat the problem, should it progress to that point. It is recommended that people with diabetes undergo a comprehensive eye examination through dilated pupils at least once a year.

What research is being conducted?

During the past 25 years, scientists have made great progress in managing and treating diabetic eye disease. Laser surgery, cataract surgery, and glaucoma medications and surgery have all been either developed or improved considerably during this period. But if this research progress is to continue, additional understanding is needed of the cellular and biochemical basis of each disease.

For example, NEI scientists have developed the first animal research model for advanced (proliferative) retinopathy. This model will allow researchers to study better the vascular changes associated with this disease. It will also allow them to initiate studies on new drugs that are designed to prevent and treat diabetic retinopathy.

Other NEI-funded scientists are studying several growth factors to determine whether they influence the development of weak new blood vessels that proliferate in advanced diabetic retinopathy. In other studies, NEI scientists have inoculated bacterial cells with the DNA sequence that codes for the enzyme aldose reductase, which has been demonstrated as being a major mechanism by which early retinal capillary cells break down in the formation of diabetic retinopathy. The inoculated cells are yielding abundant and active aldose reductase, which is valuable for use in the development of a safe and effective enzyme inhibitor.

A well-coordinated public health effort also requires accurate data on disease prevalence, progression, and associated factors. For this reason, the NEI is supporting a long-term epidemiologic study in southern Wisconsin on diabetic retinopathy.

As science moves forward in its study of diabetic eye disease, it is likely that new treatments will be a result of basic and clinical research. Improved treatment, coupled with heightened public awareness, should go far toward reducing diabetic eye disease as a future national health problem.